The narrative surrounding young people and technology often paints a picture of effortless mastery, where every child intuitively navigates digital landscapes with expertise that amazes older generations. This dangerous oversimplification ignores the fundamental distinction between recreational technology use and educational technology requirements, between having any access and having adequate access, and between possessing devices and affording the comprehensive digital ecosystem necessary for modern education. Understanding these distinctions reveals a crisis of youth technology poverty that threatens to cement educational inequality for generations.

Recent data from the Common Sense Media research initiative demonstrates that while 94% of teenagers have access to a smartphone, only 61% have reliable access to computers suitable for homework, and merely 45% possess the combination of adequate devices, reliable broadband, and quiet study spaces necessary for effective online learning. These statistics shatter the illusion of universal youth digital access, revealing instead a fragmented landscape where zip code determines educational opportunity more than aptitude or effort.

Deconstructing the digital native myth and its harmful consequences

The concept of “digital natives” suggests that young people born after 1980 possess inherent technological abilities simply through generational timing, yet this assumption crumbles when examining actual digital literacy rates and access patterns among youth. The myth perpetuates harmful policies and attitudes that assume young people need neither support nor resources to succeed in digital environments, leading to systematic underinvestment in youth technology programs and dismissal of legitimate access concerns.

Research published by the OECD Programme for International Student Assessment reveals that socioeconomic status predicts digital competency more accurately than age, with wealthy students demonstrating technology skills 2.3 years ahead of low-income peers despite identical generational positioning. This competency gap reflects not innate ability differences but rather cumulative advantages in device access, internet quality, parental support, and exposure to educational technology applications.

The hidden economics of educational technology requirements

Modern educational expectations assume student access to a sophisticated technology ecosystem extending far beyond simple internet connectivity, yet the true costs of this digital infrastructure remain largely invisible to policymakers and educators. Understanding the complete economic burden reveals why millions of families cannot provide adequate educational technology despite prioritizing their children’s education above almost all other expenses.

| Educational technology component | Minimum cost | Adequate cost | Annual maintenance | Replacement cycle |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Laptop/desktop computer | $300 | $700 | $50 | 3-4 years |

| Reliable broadband (monthly) | $50 | $80 | $600-960 | Ongoing |

| Printer and supplies | $80 | $150 | $120 | 2-3 years |

| Software licenses | $0 (free) | $100 | $100 | Annual |

| Webcam/headset | $40 | $100 | $0 | 2-3 years |

| Study furniture/setup | $100 | $300 | $0 | 5+ years |

| Technical support/repairs | $0 (self) | $200 | $200 | As needed |

| Total first year | $1,170 | $2,590 | – | – |

These figures represent per-student costs, meaning families with multiple school-age children face proportionally higher burdens that can exceed $5,000 annually for comprehensive educational technology support. The Brookings Institution analysis calculates that providing adequate educational technology consumes 11% of median household income for families at the poverty line, compared to 1.4% for households earning $100,000 annually, demonstrating how technology costs create regressive educational barriers.

Device sharing realities in multi-child households

The assumption that household device ownership equals individual student access ignores the complex negotiations and compromises occurring in families where multiple children share limited technology resources. These sharing arrangements create cascading scheduling conflicts, reduced homework time, and psychological stress that significantly impact educational outcomes even when families technically own devices.

The martinez family device juggling act

Maria (17), Carlos (14), and Sofia (11) share one laptop purchased three years ago for $400. Maria needs it for AP coursework and college applications (3-4 hours nightly). Carlos requires access for algebra homework and science projects (2 hours). Sofia uses it for elementary assignments (1 hour). The family creates elaborate schedules, but conflicts arise when assignments cluster around deadlines. Maria often works past midnight after siblings finish, Carlos rushes through homework to free the device, and Sofia frequently completes assignments on her mother’s phone, struggling with the small screen. All three report stress, incomplete assignments, and lower grades than their capabilities suggest.

Studies from the Journal of Medical Internet Research document that device-sharing students experience 42% higher stress levels, 38% more assignment tardiness, and grade point averages 0.6 points lower than peers with dedicated devices. These impacts persist even controlling for socioeconomic factors, suggesting that device sharing itself creates educational disadvantages independent of other poverty-related challenges.

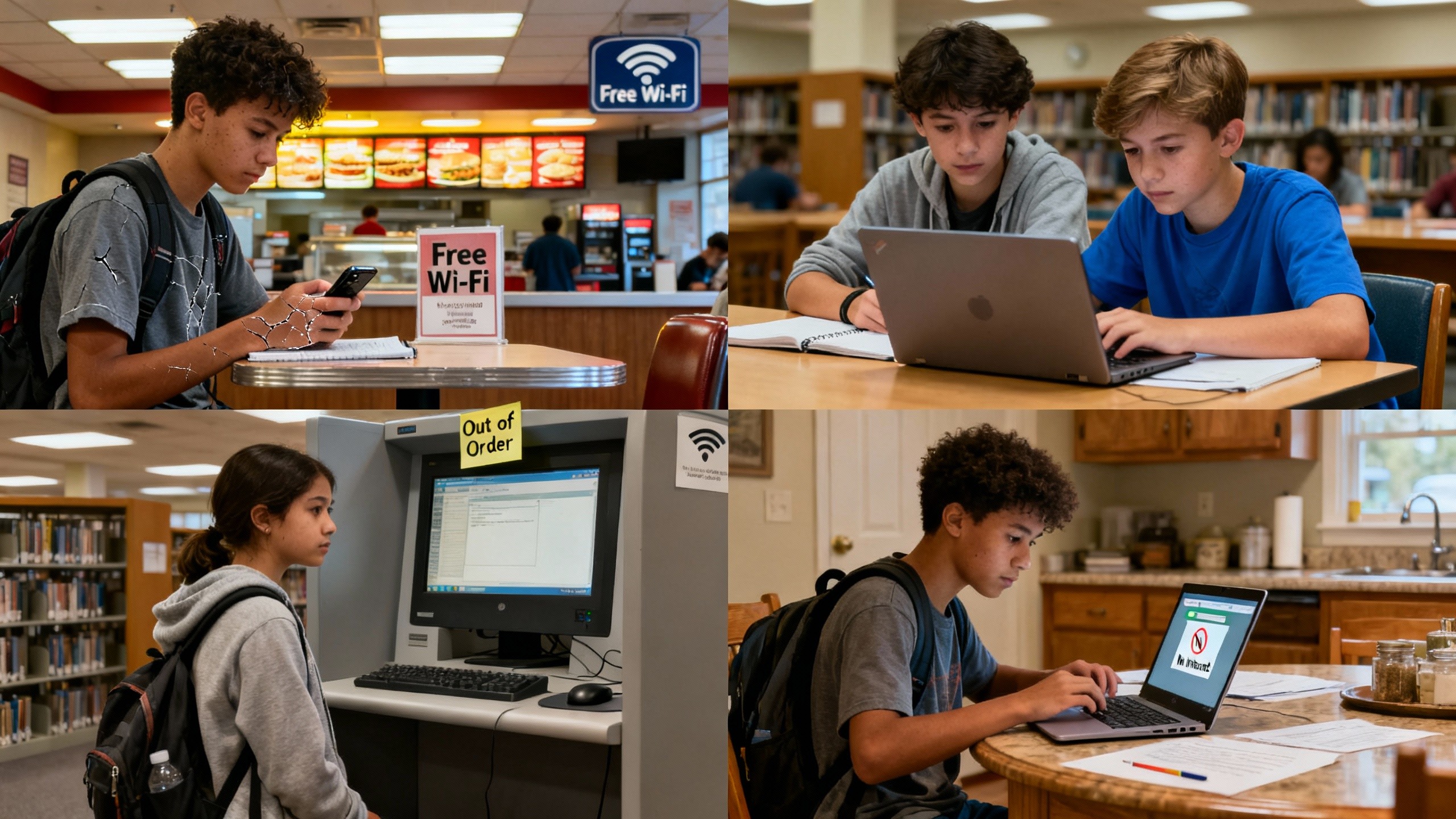

The homework gap: When home becomes a barrier to learning

The homework gap describes the divide between students with reliable home internet access and those without, but this terminology understates the complexity of barriers preventing effective home study. Beyond simple connectivity, students require quiet spaces, consistent electricity, freedom from caregiving responsibilities, and psychological safety to engage in meaningful learning, luxuries unavailable to millions of young people.

The Federal Communications Commission acknowledges that current broadband definitions (25 Mbps download/3 Mbps upload) fail to account for multi-user households where simultaneous video conferencing for school and work requires substantially higher speeds. Realistic educational requirements demand 100 Mbps for households with multiple students, yet only 41% of rural families and 58% of urban low-income families access such speeds.

Mobile-only limitations: Smartphones cannot replace computers

The prevalence of smartphone ownership among youth creates false impressions of digital equity, as observers mistake recreational device access for educational technology adequacy. While smartphones enable certain digital activities, they fundamentally cannot support the complex tasks required for modern education, creating a two-tier system where mobile-only students face insurmountable disadvantages despite technically being “connected.”

| Educational task | Computer completion time | Smartphone time | Mobile success rate | Quality impact |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5-page essay | 2 hours | 5.5 hours | 61% | -35% score |

| Research project | 3 hours | 8 hours | 44% | -42% score |

| Math problem set | 1 hour | 2.5 hours | 73% | -28% accuracy |

| Science lab report | 1.5 hours | Cannot complete | 0% | Fail/incomplete |

| Group presentation | 2 hours | 6 hours | 38% | -51% score |

| Coding assignment | 2 hours | Cannot complete | 0% | Fail/incomplete |

Geographic disparities: Urban myths and rural realities

Technology poverty affects both urban and rural youth, but manifests differently across geographic contexts in ways that complicate uniform policy responses. Urban students often have theoretical infrastructure access but face affordability barriers, while rural students encounter absolute absence of broadband options regardless of financial resources. Understanding these geographic variations reveals why single-solution approaches consistently fail to address youth technology poverty comprehensively.

Data from the BroadbandNow research initiative reveals that FCC coverage maps overstate broadband availability by 42%, with rural areas showing the largest discrepancies between reported and actual access. This misrepresentation leads to systematic underfunding of infrastructure programs while creating false narratives about technology access that harm students unable to connect despite official claims of coverage.

The psychological toll of technology inadequacy

Beyond immediate educational impacts, technology poverty inflicts profound psychological damage on young people who internalize their struggles as personal failures rather than systemic inequities. The daily experience of watching peers effortlessly complete digital tasks while struggling with inadequate tools creates shame, anxiety, and learned helplessness that persist long after immediate technology barriers are addressed.

Research published in Computers & Education journal documents that students experiencing technology poverty report depression symptoms at rates 2.7 times higher than adequately resourced peers, with 68% describing feelings of hopelessness about their educational futures. These psychological impacts create feedback loops where emotional distress further impairs academic performance, reinforcing beliefs about personal inadequacy that obscure structural inequalities.

School-provided devices: Promise versus reality

Many districts implement one-to-one device programs intending to eliminate technology disparities, yet these initiatives often fail to address the full spectrum of barriers facing low-income students. While device provision represents progress, implementation challenges and hidden requirements frequently perpetuate rather than eliminate digital inequities.

Common failures in school device programs include requiring families to pay insurance fees ($50-150 annually) that low-income households cannot afford, blocking educational websites and tools students need for homework, implementing monitoring software that invades privacy and creates stress, providing outdated devices that cannot run current software, and limiting device use to school-related activities, preventing skill development. These restrictions mean that even students with school-provided devices may still lack adequate technology access for comprehensive learning.

The hidden curriculum of digital inequality

Technology poverty teaches powerful lessons beyond missing homework assignments, embedding beliefs about social position, future possibilities, and self-worth that shape life trajectories. Students learn that their families are deficient for failing to provide “basic” tools, their communities don’t matter enough for infrastructure investment, their struggles are individual rather than systemic, and their futures exclude careers requiring digital fluency. This hidden curriculum of digital inequality prepares youth for subordinate social positions while appearing to offer equal opportunity.

| Hidden lesson | Student interpretation | Long-term impact | Societal cost |

|---|---|---|---|

| “Technology isn’t for people like us” | STEM careers impossible | Avoided technical fields | Lost innovation potential |

| “We must be less capable” | Internalized inferiority | Reduced aspirations | Perpetuated inequality |

| “Working harder isn’t enough” | Effort doesn’t matter | Learned helplessness | Reduced productivity |

| “The system is rigged” | Legitimate grievance | Disengagement | Social instability |

| “Education isn’t the answer” | School irrelevant | Early departure | Reduced human capital |

Long-term economic consequences of youth technology poverty

The immediate educational impacts of technology poverty translate into lifetime economic disadvantages that perpetuate intergenerational inequality. Students who cannot develop digital skills during critical learning periods face permanently reduced earning potential, limited career options, and decreased economic mobility that affects not only individual futures but entire community trajectories.

The transition to remote and hybrid learning during COVID-19 created a natural experiment demonstrating these long-term impacts in accelerated timeframes. Students lacking adequate technology during 2020-2021 show learning losses equivalent to 1.5 academic years, with recovery projections suggesting that many will never fully catch up to pre-pandemic trajectories. These educational scars will manifest as reduced college enrollment, lower degree completion, and diminished career prospects that reshape entire generational cohorts.

Innovative solutions that work within existing constraints

Despite systemic challenges, innovative programs demonstrate that youth technology poverty can be addressed through creative approaches combining community resources, corporate partnerships, and student agency. Successful interventions recognize that solutions must be locally designed, culturally relevant, and sustainable without depending on uncertain funding streams or political will.

The Digital Promise Verizon Innovative Learning initiative demonstrates scalable solutions providing devices and connectivity to under-resourced schools. Their model combines device provision with teacher training, family engagement, and ongoing support, achieving 92% sustained usage rates and measurable improvement in student outcomes. Key success factors include treating technology as tool rather than solution, embedding support within existing relationships, and measuring success through educational rather than connectivity metrics.

Policy failures and political obstacles

Current policies addressing youth technology poverty suffer from fundamental misunderstandings about the nature of the problem, focusing on infrastructure rather than accessibility, connectivity rather than capability, and individual rather than systemic solutions. These policy failures reflect both genuine confusion about digital inequality’s complexity and deliberate choices prioritizing corporate interests over student needs.

Creating sustainable solutions at scale

Addressing youth technology poverty comprehensively requires systemic interventions that recognize technology access as educational infrastructure equivalent to textbooks or transportation. Sustainable solutions must address immediate needs while building long-term capacity, combining public investment with community ownership and corporate accountability.

The philadelphia model: Comprehensive digital equity

Philadelphia’s digital equity initiative demonstrates integrated approaches addressing multiple barriers simultaneously. The program provides: free or $10 monthly internet for qualifying families, refurbished computers for $50-150, digital literacy training in multiple languages, technical support through community centers, and youth digital ambassador programs creating peer support networks. Results after three years show 67% reduction in homework gap, 41% improvement in graduation rates for participating students, and $4 return for every $1 invested through improved educational outcomes.

Frequently asked questions about youth technology poverty

Conclusion: Confronting uncomfortable truths about digital inequality

Youth technology poverty represents not unfortunate circumstance but deliberate policy choice, reflecting societal decisions about whose education matters and which communities deserve investment. The assumption that young people naturally navigate digital environments obscures systematic exclusion of millions from educational opportunity, creating elaborate justifications for inequality that blame individual families for structural failures.

Addressing this crisis requires abandoning comfortable myths about digital natives and technological meritocracy, instead acknowledging that technology access constitutes essential educational infrastructure that society must provide universally. The same logic that demands public schools provide textbooks should ensure students have devices and connectivity for homework. The principle ensuring transportation to school should guarantee digital pathways to learning.

The evidence overwhelmingly demonstrates that youth technology poverty perpetuates intergenerational inequality, limits economic mobility, and wastes human potential on massive scales. Every year of delay condemns millions of students to permanently diminished opportunities, creating educational scars that persist throughout lifetimes. The question is not whether we can afford to address youth technology poverty, but whether we can afford to continue ignoring it.

Solutions exist, from community technology hubs to universal broadband provision, from comprehensive device programs to family digital literacy initiatives. What’s missing is not knowledge or resources but political will to prioritize equity over profit, to recognize education as public good rather than private commodity, and to ensure that every young person, regardless of zip code or family income, can access the digital tools essential for modern learning. Until we summon that will, millions of youth will continue experiencing poverty not of their making, struggling with barriers not of their choosing, and suffering consequences that diminish us all.

Leave a Reply